Limited Edition Portfolio, 2006Artists: Marina Abramovic, Janine Antoni, Hans Georg Berger, Cai Guo-Qiang, Ann Hamilton, Dinh Q. Lê, Jun Nguyen-Hatsushiba, Shirin Neshat, Vong Phaophanit, Allan Sekula, Shahzia Sikander, and Rirkrit Tiravanija The Quiet in the Land is pleased to announce the publication of a limited edition portfolio produced in conjunction with the third project in The Quiet in the Land series conceived and organized by the contemporary art curator and art historian France Morin. The portfolio is published in an edition of fifty, numbered 1 to 50, plus sixteen hors commerce (HC), numbered I to XVI, and two printer’s proofs. Each portfolio includes twelve photographic diptychs produced specifically for the project by twelve of the participating artists. Each of the twenty-four photographs is a 11 x 14 in. (28 x 35.5 cm) C-print. Eight diptychs are printed on crystal archive photographic paper (Abramovic, Antoni, Cai, Hamilton, Lê, Nguyen-Hatsushiba, Phaophanit, Sekula, and Tiravanija). Four diptychs are pigment prints on Hahnemühle paper (Berger, Hamilton, Neshat, and Sikander). Each diptych is signed, numbered, dated and/or titled by the artist on bottom verso. The photographs are presented in a clamshell box covered in handwoven silk designed by Carol Cassidy, internationally acclaimed founder of Lao Textiles, Vientiane, Lao PDR. The box’s clasp is designed by Lorenz Bäumer, famed Paris-based jewelry designer. It is presented in a pouch of handwoven silk designed by Cassidy. The printer is Laumont Editions, New York. The purchase price for each portfolio is US$15,000. To purchase a portfolio, please complete a purchase form and mail it to the address indicated. Please direct any inquiries to France Morin at fmorin5627@aol.com. For a purchase form, please click here. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

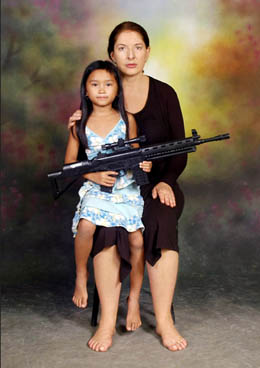

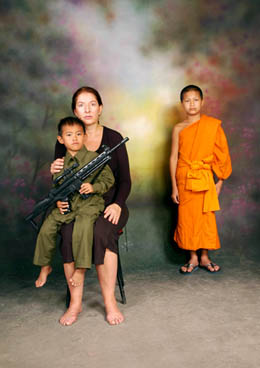

MARINA ABRAMOVIC The Family These photographs are inspired by the complex and contradictory relationship between communism and Buddhism that Abramovic perceived in Laos, which reminded her of her personal experience of the relationship between these belief systems. Abramovic was born in the former Yugoslavia shortly after the end of World War II. Her father was a general and national hero; her mother, an army major and director of a revolutionary art museum. After her birth, her parents gave her to her grandmother, a devout adherent of the Serbian Orthodox faith who disliked communism. With her grandmother, she would participate in Serbian Orthodox ceremonies. Later, when she returned to her parents, she received strict instruction in communist ideology. After she left the former Yugoslavia, however, she became involved with Tibetan Buddhism, which has remained important to her to this day. Thus, during her formative years, she personally experienced the challenges of living in a family and a culture shaped by belief systems that did not always elide with one another. In Laos, she perceived a similar phenomenon. After the communists assumed power in 1975, the government espoused tolerance of Buddhism by teaching that it was complementary with communism, yet the number of boys and men who were ordained declined. With political liberalization, this situation has changed, but the relationship between communism and Buddhism has remained tense. Identifying with this tension, Abramovic titled her photographs, shot in a photography studio in Luang Prabang, The Family and portrayed herself as a maternal figure to two Lao children. In one image, a boy dressed in military fatigues and holding a toy machine gun sits in her lap, while a novice stands in the background. In the other, she holds a girl dressed in everyday civilian clothes, also holding a toy machine gun. |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

JANINE ANTONI Branch | Tributary Antoni has described Branch and Tributary as follows: “Branch is made from a traditional stencil that is used to make gold imagery on temple walls. In this photograph, the stencil acts as a window onto the landscape. It takes the traditional motif of the figure in the landscape but renders the figure transparent. It is clear that the red paper was laid over an image of a landscape; however, by printing them together, the figure and landscape literally become one. Tributary is a photograph of the mirrored mosaic on the facade of Vat Xieng Thong. On close inspection, one notices that trees are reflected in the little mirrored tiles that make up the figure. At the center of the figure, there is a reflection of a mosaic tree from an adjacent temple. In contrast to Branch, the figure incorporates the landscape through reflection rather then transparency. My intention is to show two different paths to the same point: interconnection. Thus, the titles are synonyms and therefore echo this sentiment. This feeling of interconnection is one of the great gifts of Theravada Buddhism.” |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

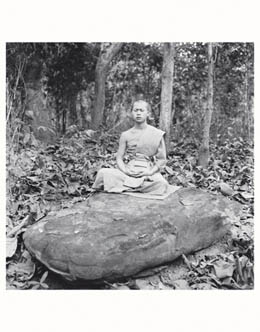

HANS GEORG BERGER Meditation Color 1 | Sitting Meditation 2 In December 2004, the Sangha (Buddhist community) of Luang Prabang organized a meditation teaching retreat for over 400 monks and novices in a forest on the city’s outskirts. In 2005, the Sangha organized a second retreat attended by over 500 monks and novices. The purpose of these retreats was to strengthen the Sangha—which has been challenged by the growing intrusion of the Internet, the English language, tourism, and other changes wrought by globalization on traditional spiritual practice and discipline—by reintroducing Vipassana. Vipassana is a Lao meditation practice that had been in partial abeyance since 1975. At the retreats, the elder monks instructed the younger ones in the fundamental concepts and practices of Vipassana, thus helping to ensure the survival both of this tradition and of the Sangha itself. The Sangha invited Berger to participate in the two retreats as an artist-documentarian. As he has written, “the goal was not only to document meticulously the particularity of Luang Prabang’s meditation tradition, but also to empower all participants and their spiritual practice through the photographic process.” Accordingly, applying an aesthetic practice he has termed “community involvement,” he did not produce spontaneous snapshots of his subjects, but planned black-and-white photographs using an analog Hasselblad middle-format camera. In these photographs, he gave the individuals portrayed “the last word in a subtle, carefully orchestrated process of choice, discussion, and shared decision on the value and importance of the images produced.” For the first time in his career, he also shot a select number of photographs in color with a digital camera. Meditation Color 1, one of these color photographs, portrays an orange robe worn by a monk or novice; an almost abstract field of saturated color, the robe is drying in the wind after having been washed. Sitting Meditation 2 portrays a solitary novice who seems to be floating as he meditates on a rock in the forest. |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

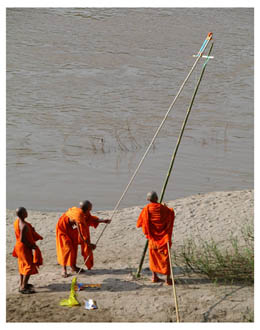

CAI GUO-QIANG Homemade Missile Cai’s photographs portray a group of monks and novices in Luang Prabang launching rockets over the Mekong River during Boun Ok Pansa, a Buddhist festival that celebrates the end of Lent, the period every year when the city’s monks and novices remain inside their monasteries. Cai is perhaps best known for the drawings and events he creates by exploding gunpowder, which the Chinese invented in the tenth century (his birthplace, Fujian Province, is famous for the manufacture of firecrackers). When he traveled to Salvador, Brazil, for the second project of The Quiet in the Land, for example, he developed a project involving gunpowder, in collaboration with a group of former street children, most of whom were African-Brazilian. Intrigued by the cannons in Salvador’s historical forts, he wanted to deepen the children’s understanding of the causes of racially motivated violence and to reclaim a symbol of destruction as one of hope. Under his guidance, the children built inventive cannons based on drawings they had made, and they fired these cannons at the opening of the project exhibition in a celebratory fusillade. When Cai traveled to Luang Prabang in October 2005, he was similarly intrigued by another way in which individuals used gunpowder in a celebratory manner: the launching of rockets by monks and novices during Boun Ok Pansa. The monks and novices produce the rockets by tamping homemade gunpowder into bamboo stalks, and they fire the rockets all day during the festival. Rockets are considered to be busa (offerings) sent into the heavens to honor Lord Buddha. They also are believed to sweep away evil influences and are connected to the death of the Buddha, when divinities sent a rocket to ignite his cremation pyre. |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

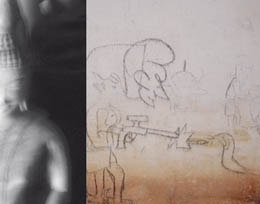

ANN HAMILTON Luang Prabang, Laos, August 2005 During her first visit to Luang Prabang, Hamilton was moved by the flow of the Mekong River, which she described as a “visual embodiment and confluence of cultural currents, where a traditional past mixes with the modern present.” She also visited four monasteries near the city, which feature long, narrow chambers designed for walking meditation. Inspired by these structures, she designed for the monks and novices a boat for spiritual meditation. Her photographs relate to some of the sources that inspired the Meditation Boat: an image of a boat from a painting in Vat Long Khoun, a temple with a restored walking meditation chamber; an image of a Buddha from the Pak Ou Caves on the Mekong River 25 kilometers from Luang Prabang, which are filled with scores of Buddhas left as offerings by the people; and an image of graffiti on the wall of an old tobacco factory outside of Luang Prabang. Hamilton has observed that the two images on either side of the Buddha image respectively evoke the choice to undertake the journey that the Buddha taught (and in the process to change ourselves and the world for the better) and the choice to resist this journey for the easier work of violence. These choices do not exist in opposition, but instead mediate and transform one another in confluence, like the currents of the Mekong. |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

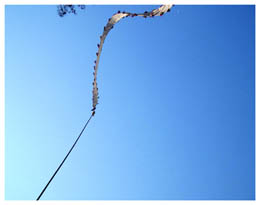

DINH Q. LÊ The Banners of Luang Prabang Lê made the following observation on his visits to Luang Prabang: “I found a community that is going through a very difficult and confusing transitional process. They are under conflicting pressure from all sides to change, to modernize and yet also to stay the same.” Inspired by this tension, he and Nithakhong Somsanith, one of the only active practitioners of the Lao courtly art of gold-thread embroidery, which he learned as a child, developed a project in collaboration with Catherine Choron-Baix, an anthropologist who has studied Lao culture for many years. For their project, Lê and Somsanith made three large works of embroidery on silk. These works feature motifs omnipresent in the city that respectively evoke tradition and modernity, including funeral banners and satellite dishes. For his photographs, Lê focused on the banners. These banners are long bamboo poles; a fabric banner is attached to the top of the pole, and a sculpted image of a fish, bird, or, more recently, airplane is often attached to the end of the banner and is carried aloft by the wind. In Lao funeral rites, these banners are meant to help the deceased find their way to the other world. After the rites have been completed, the banners are left to deteriorate. In this respect, they signify the process of birth, decay, and death. For Lê, they evoke not only the death of the body, but the death of some traditions as they are being replaced by new ones. |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

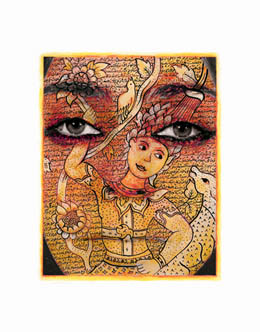

SHIRIN NESHAT Untitled In 1993, Neshat began a series of photographs entitled the Women of Allah. In these black-and-white photographs, she depicted herself, sometimes with others, wearing the chador (veil). In many images, her face, hands, feet, and other exposed body parts are inscribed with love poems by Persian poets written in Farsi, the language of Iran, her native country. The photographs that comprise Untitled relate directly to this body of work. While visiting Luang Prabang in November 2005 with Shoja Azari, Neshat began to perceive parallels between Iran and Laos, particularly with respect to tensions between the past and the present, the traditional and the contemporary. The photograph on the left features three images layered one on top of another: an image of an Iranian man, a text written in Farsi by an Iranian from Laos about Laos, and an image from a temple reproduced from the writer Francis Engelmann’s book, Luang Prabang: Capital of Legends (1997). The photograph on the right also features three layered images: an image of Neshat herself, the above-mentioned text, and another temple image reproduced from Engelmann’s book. |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

JUN NGUYEN-HATSUSHIBA These photographs are inspired by the film that Nguyen-Hatsushiba produced for the project. Shot on location in Luang Prabang with the participation of over fifty art students from the Luang Prabang School of Fine Arts, this film asks how the growing influence of international pop culture, including the brand-name products that materialize that culture, such as American products like Nike and Chinese-made knock-offs like Meike, will shape the shifting values of traditional youth culture in the city. The photographs relate specifically to the first part of the film, which Nguyen-Hatsushiba shot in Luang Prabang National Stadium. This part features about fifty runners preparing to jog around the stadium’s track. Each runner wears a pair of Meike running shoes. For Nguyen-Hatsushiba, “[t]he stadium is a microcosm, and the act of running around the track is a metaphor for the pace at which Lao society is struggling to train to rise. The open-air stadium functions as a sanctuary uniting the ground and the sky, extending the hopes of the runners as they train. Nevertheless, this structure obligates the runners simply to go around and around, ticking moments.” |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

VONG PHAOPHANIT Blue Hut 2006 | Green Reflection 2006 These photographs relate to All that is solid melts into air (Karl Marx), a 35-minute film in Lao with English subtitles, which Phaophanit produced for the project. Claire Oboussier wrote the voiceover. Even though he was born and raised in Laos, Phaophanit had not visited Luang Prabang prior to the project. Thus, as he has observed, “I started from the knowledge that I knew very little of the city. In this sense, the film can be seen as an antidote to the tradition of didactic documentary film-making. It explores the minutiae of the city, touching on intimacy and on that which we normally might not notice.” A poetic collage of images and sounds captured on his two visits to the city in April 2005 and April 2006, it explores the complexities and contradictions of a place in transition. The title derives from Karl Marx’s famous words from the Communist Manifesto (1848) on the nature of modernity: “All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real condition of life and his relations with his kind.” The spirit of these words resonates throughout the film, as Phaophanit asks what it means to be modern in Luang Prabang, a city that is changing day by day as it opens up to the rest of the world. |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

ALLAN SEKULA B-52 Crater | Whisper Sekula visited Luang Prabang and the region surrounding the city in October 2005 and January 2006. During his visits, he shot footage for a film, titled A Short Film for Laos (2006), as well as a series of photographs. Two of the photographs are B-52 crater, which depicts a bomb crater in the Plain of Jars, a region of Laos pockmarked with craters from bombs dropped during the Vietnam War, and Whisper, which portrays a Lao village woman whispering to a friend. Describing these photographs, Sekula has written: “B-52 crater is the third photograph I have made comprised of a ‘split-basin,’ that is, a circular depression seen at an oblique angle so that it appears as an oval or ellipse and is divided evenly between two frames down the middle. The other two are Doomed fishing village of Ilsan (1993) from Fish Story and Oil recovery pit, Lendo (2002) from Black Tide. The divided frame is a way of ‘domesticating’ a topographic feature, more or less treating it like a kitchen sink. The residual violence recorded in B-52 crater, the thirty odd years that have passed since the ear-blasting shock of the explosions (one was lucky to lose only one’s hearing), leads to Whisper, a moment of inaudible private conversation between two Lao village women. This is one of a number of photographs I have made in which listening or speaking is central, such as Dockers listening (1999) from Freeway to China.” |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

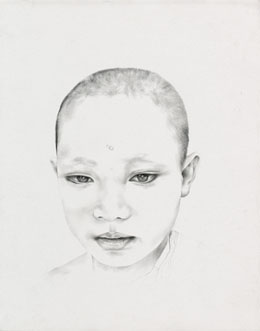

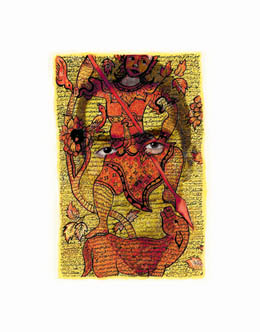

SHAHZIA SIKANDER Novice Chanton | Naga Sikander made two visits to Luang Prabang for the project, in November 2005 and July 2006. During these visits, she developed two bodies of work: Portraits and Sinxay. As she has written, for “the Portraits, I took photographs of Phra Acharn One Keo Sitthivong, the Abbot of Vat Pakkhane and Vat Xieng Thong Volaviharn and Director of the Buddhist Schools in Luang Prabang, as well as of six monks and twelve novices from both monasteries to capture each face. I also spent time with the novices explaining and demonstrating the technique of the work. Afterwards, I made portraits based on the photographs in the style of photorealism. Requiring solitary patience, each portrait took a few days of intense labor with various graphite pencils, a very economical means of working. An homage to each novice and monk in Luang Prabang, the portraits give individuality to them in a city in which tourists often only see them collectively as ‘the longest line of monks in the world making the morning almsround.’ In this respect, drawing for me became a very spiritual and humbling act.” Novice Chanton portrays one of the novices with whom Sikander collaborated for the Portraits series. Naga, by contrast, relates to the group of eight paintings on paper that comprise Sinxay, which were inspired by the epic poem of the same name by Pangkham, a masterpiece of Lao literature. As Sikander has observed, “Having worked in depth with the tradition and techniques of Indo-Persian miniature painting, I was particularly excited to recognize the visual links in the Lao mythological iconography to Hindu religious narratives. I found some images particularly alive and multidimensional in Luang Prabang, such as the naga (especially the various sculptural renderings).” According to traditional Lao beliefs, nagas are serpent-like creature that live in the Mekong River and serve as protectors of the Lao people. Prominently featured in Lao iconography, they are most often found on both sides of the stairs leading into a temple. They are intimately connected to the changes of the seasons and to the yearly monsoon, when water floods the fields and makes possible the cultivation of rice. |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

RIRKRIT TIRAVANIJA Untitled 2006 (One Thousand Buddhas) Tiravanija’s photographs relate to his artist project. In an antique shop in Chiang Mai, Thailand, he found a small wooden carving of a Buddha in the Lao and Northern Thai style. A master carver and a craft workshop in Chiang Mai carved one thousand replicas of this Buddha in various sizes. Tiravanija then brought these Buddhas to Luang Prabang. It is anticipated that he, the master carver, and Lao master carvers will work with a UNESCO-sponsored project that trains monks in traditional artistic practices to create another thousand Buddhas. The Thai- and the Lao-produced Buddhas will then be offered to 24 monasteries throughout the city. This gesture may be conceived in part as a humble effort to bridge the often troubled relationship between the two states now known as Laos and Thailand. In 1707, for example, the ancient Lao kingdom of Lan Xang was broken up into three Siamese vassal kingdoms at Luang Prabang, Vientiane, and Champasak. After a period of Burmese domination, these kingdoms were reconquered by the Siamese in the late eighteenth century—a period of rule that ended only with the arrival of the French colonizers in the late nineteenth century. Today, even though Laos is an independent state, it still must confront the economic might of the “Asian Tiger” to its west, exemplified by the influx of Thai products and of Thai soap operas and other television programs received on the satellite dishes now ubiquitous in Luang Prabang. In this respect, Tiravanija’s creation of Buddhas in the Lao and Northern Thai style, by both Lao and Thai artisans, points to a shared cultural tradition that transcends boundaries, and his offering of these Buddhas to the monasteries of Luang Prabang can be interpreted as a gesture of reconciliation. |

|||||||||

|

|